Every Goodwood race, parade, demonstration and display is carefully curated but sometimes stories arise that have had no planning and are pure motorsport serendipity. At the 80th Members’ Meeting, such a meeting occurred so we thought it prudent to mark the occasion as the circles in which they move are quite different and their meeting again in the future is far from certain.

On appearance alone, it is difficult to imagine what thread stitches the histories of these two cars together. The 1911 SCAT is from the ‘Heroic’ days of Edwardian racing and the Porsche 911 Carrera RSR from the hairy-chested professional melee of the 1970s. The S.C.A.T. (Società Ceirano Automobili Torino) is throw-back to the exciting dawn of motorsport, where every engineering decision was an educated guess and every driving decision was a leap of faith. It is a riot of brass dials and leather straps, the seats are part-wicker and the headlights look like they were designed by Jules Verne. It is a far cry from the sculpted lines, wings and scoops of the Porsche 911 RSR, resplendent in its beloved Martini livery.

Those among you that have done your homework however might guess at the connection, having recognised the #8 1973 911 RSR as that of Herbert Müller and Gils van Lennep and the car that won the last World Championship version of motorsport’s longest-running and toughest road race, the Targa Florio.

The story of the Targa Florio begins with a young Sicilian, Vincenzo Florio, who was characteristic of many early motoring enthusiasts. Young, modern and independently wealthy he was free to indulge his fascination with all things mechanical. Bicycles were his first obsession and he amassed an enviable collection from the world’s best manufacturers. So it is perhaps unsurprising that when his elder brother, Ignazio, introduced him to a De Dion-powered tricycle his interest became an obsession. No sooner than had he got his new machine running (a telegram to Paris was required to understand what made it go as no one had yet heard of petrol in Sicily), Vincenzo sought competition. As his tricycle was the only powered machine on the island his only options were a man on a bike and a horse. He lost to the horse but his obsession for racing was cemented.

His first race in 1902 on a Panhard et Levassor was a sprint event in Padua where he won against stiff competition from Cagno and Lancia. Fortuitously his older brother thwarted an attempt to enter the fateful 1903 Paris to Madrid race but on coming of age Vincenzo was free to indulge his passion for racing in the many hill climbs, sprints and races that sprang up across Europe.

It was perhaps inevitable that with his connections, wealth and experience that Vincenzo would be instrumental in bringing racing to Italy, which he did in 1905 with the Coppa Florio. But Vincenzo had inherited from his powerful family a fervent love of his homeland and believed not just in the glory of racing but in putting Sicily firmly on a global stage. Which he undeniably did with the Targa Florio.

Organising any new event, even in the modern period, is fraught with challenges. Creating a race on an island that has no cars or roads however is on another level, especially when you consider that local permissions have to be sought not only from bureaucratic councils and angry farmers but also from the Mafia .

The first route that was chosen was 90 miles long and rose over 3600 feet into the Madonie mountains. The road throughout was nothing but mule track, unprotected, unsigned, tortuously and unendingly twisting through mountainous farmland. The Targa Florio is defined like no other race (not even the Nürburgring comes close) by its innumerable corners. Apart from the 3.7 mile Buonfornello straight, it is all corners, some estimate the early circuit had nearly 2000 of them – roughly 20 corners per mile. Many of the corners were precipitously high hairpins and barriers had not been invented, only thick stone walls. In his book ‘Targa Florio’, W.F. Bradley paints a vivid picture; ‘Under more pampered civilisation there would have been one long road sign, 90 miles from end to end, with the word D-A-N-G-E-R inscribed upon it in blood red letters’. There was no petrol, there were no garages, no engineers, no service stations, wandering livestock risked getting entangled in axles and there was always the nagging question of how best to deal with the armed bandits. The early races were truly adventurous.

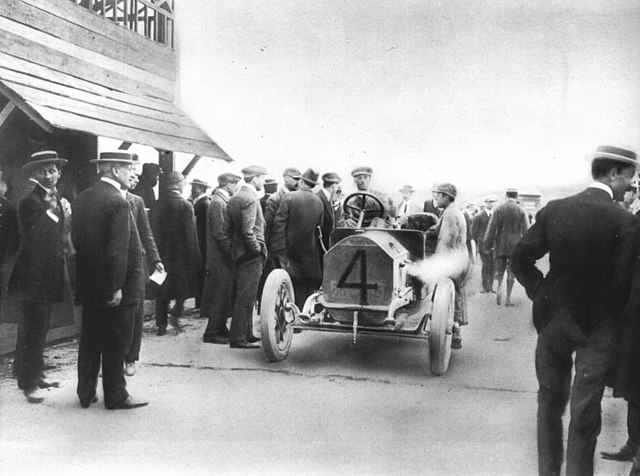

The first race in 1906 was won by Alessandro Cagno on an Itala having completed 3 laps of the 90 mile circuit in 9 hours 32 minutes and 22 seconds making his average speed 29.08 mph. If that sounds slow take a moment to consider what average speed a modern car displays driving on smooth motorways and sanitised roads through town, with ABS, traction control, power steering and a windscreen. If the frequency of tyre changes is taken into consideration (some cars carried 8 or more spare tyres ) and the shattering 20-30 minutes of physical labour they demanded then 29.08mph becomes astonishing.

Andrew-Howe Davies’ 1911 S.C.A.T. is not the car that won the Targa Florio in 1911, that exact car no longer exists, but it is a genuine SCAT 22/32 chassis with the correct running gear and an American 9 litre Simplex engine and it is presented very much in the way that it would have appeared on the start line in Cerda 112 years ago. Then it was driven by Giovanni ‘Ernesto’ Ceirano, one of four remarkable brothers, shaped from the same futuristic mould as the irrepressible Vincenzo Florio, whose lives were interwoven with the history of both the Targa Florio and the Italian car industry.

The Ceirano’s were involved with racing from the outset. The eldest brother Giovanni Battista entered his own motorised bicycle in a race from Turin to Asti as early as 1895 but their impact on the early Italian car industry went much further than that. Both directly and indirectly the ideas and creations of ‘Giovan’, Ernesto, Giovanni and Matteo could be found in Fiat, Itala, S.C.A.T., S.P.A. Ceirano and S.T.A.R. cars. Indeed six of the first nine Targa Florios were won by machines that Ceirano’s had influenced or designed. S.C.A.T.s won the race three times and in doing so secured their place in the history books but perhaps their most memorable victory was in 1912.

Cyril Snipe was the nephew of a Manchester car dealer, John Bennett of Newton-Bennett, who were agent for S.C.A.T. in the UK. Snipe worked in Turin with the Ceirano brothers and was chosen as their pilot for the 7th Targa Florio. Almost unbelievably, the route in 1912 circumnavigated the entire island of Sicily, 1 lap of 656 miles. Snipe drove the whole thing himself with his Italian riding mechanic Pardini. Having started in the early hours of Saturday morning he found himself beyond exhaustion as the race neared its conclusion. Unable to drive another yard he practically fell from the driver’s seat into a deep slumber at the side of the road. Pardini, after some 2 hours had elapsed, realised that no other competitors had passed and gently revived his pilot with a bucket of icy water. Enraged but undoubtedly awake, Snipe returned to the driver’s seat and won. His race took 23 hours and 37 minutes at an average of 24.3mph and he never drove the same corner twice.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the Ceirano brothers planted the seeds from which the entire Italian motor industry grew. They enjoyed racing success with S.P.A. and Itala winning the Targa Florio, the Coppa Florio and the epic Paris to Peking race in 1907. They discovered for themselves the link between winning races and selling cars, which manufacturers continue to pursue today and in fact, it was very much that incentive that drove the Porsche 911 RSR to victory in 1973.

Ferdinand Porsche’s innovations were driving development in the early 1920s and it was at the Targa Florio that he debuted DMG’s supercharged Mercedes which was driven to victory by Christian Werner. It was after the war however that the Porsche name became synonymous with the Targa Florio.

Unlike their early Italian counterparts who were driven by a wild enthusiasm and a pioneering creative spirit, Porsche’s racing success was a result of perseverance and logical engineering progression. The Ceiranos and Florios had money to invest in their passion, but after the war, Porsche was nearly bankrupt and racing success was a marketing necessity. Funded by Ferdinand Piech from the royalties of VW Beetle sales, Porsche’s racing programme was defined by simplicity, attention to detail, fastidious preparation and lots of testing but it wasn’t long before its efforts were rewarded, the first notable successes came with the 550 variants with wins at the Carrera Panamericana in 1954 and the Targa Florio in 1956. Porsche then dominated in Sicily with 718s, the 904, the Carrera 6, the 910, 907, and 908 each new development and design building on the lessons of its predecessor. The 908 was a purpose-built weapon for the Targa Florio with its power and weight distribution perfectly matched to the twisting, undulating course, making the Ferraris and Alfas look cumbersome by comparison. Changes to the Group 5 rules, however, rendered Porsches uncompetitive, the 917 engine being too big and the 908 being too light, forcing the company to abandon its top-flight Sportscar racing programme.

Porsche’s attention turned to the 911 and GT racing. Launched in 1972 the new RSR was a massive hit and proved reliable on track. To stay competitive though Norbert Singer made several ‘creative’ modifications which by Vallelunga that year proved too much for the officials. In a bizarre twist of fate though Singer was given the option to enter the 911 RSR as a Group 5 prototype, meaning that Porsche could keep racing, disgruntled RSR customers (whose cars weren’t as quick as the modified works machines) could be appeased and Singer kept his job.

At the Targa Florio fortune continued to favour the team from Stuttgart as mechanical failure and driver error eliminated the Ferrari and Alfa Romeo front runners gifting the last World Championship Targa Florio victory to the venerable 911. Singer and his team once again proved that; ‘to finish first, first you have to finish’. It may not have been a vintage battle but, with 10 previous wins, it secured Porsche as the manufacturer with the most wins at the Targa Florio and forever bound their names together. An outright win at Daytona for the Brumos RSR proved it was no fluke either.

The Targa Florio continued for another four years as a non-championship event but the writing was on the very close wall covered in spectators. 700,000 turned up in 1973. The Targa Florio, perhaps because it was so tortuously twisting and not a flat-out speed circuit, had a comparatively good safety record. Speed continued to build thought with cars now averaging almost 80mph on the dusty, Sicilian lanes and with no meaningful way of protecting the spectators on the 277 mile route the likelihood of a horrendous incident seemed inevitable. In 1977 the fear became reality, Gabrielle Cuiti’s accident claiming the lives of two spectators and seriously injuring several more.

The story of every Targa Florio was packed with adventure, courage, madness, despair, endurance, companionship, rivalry, passion and probably lots of good Sicilian wine. We’ve said nothing here of Chiron and Varzi’s ferocious battle in 1930. The lead passed between them constantly in a frenetic chase. So determined was Varzi that his mechanic was forced to fuel the car as it bounced along the rough Sicilan roads and in doing so set light to the overworked Alfa Romeo P2 and its driver – slightly toasted but undeterred Varzi drove on to victory. We haven’t mentioned Moss securing Mercedes’ final world sports car championship in 1955 or his sister Pat racing without shoes for faster footwork. We could replay Vic Elford’s sensational win in his Porsche 907 in ‘68 or Helmut Marko’s electrifying lap record. And what of the beloved school teacher from Palermo, Nino Vacarella, winning in front of 500,000 feverishly excited Sicilians in the beautiful, screaming Ferrari 275 P2 at the zenith of the swinging ‘60s? Look up ‘nostalgia’ in the dictionary and I imagine you’ll see that picture.

Until its last moments, the Targa Florio was a test of strength and endurance. It asked every driver: ‘How much do you want this? Just how passionate are you about winning?’ Other races were developed, and got smoother, wider and safer but the Targa remained an unforgiving assault of corners in rain, snow and blazing heat. The passion of its drivers, like no other motor race, was met and often eclipsed by the maniacal enthusiasm of the local population. What other motor race connected so fiercely generations of men, women and children from every walk of life?

The S.C.A.T. and the Porsche that met at Goodwood are different in every possible way. The S.C.A.T. was born of a passionate, creative impulse and an obsessive compulsion to race; the Targa winning 911 was a reluctant response to officialdom, corporate pressure and a purposeful engineering philosophy. One very Italian and one very German. The truth is that there is very little to connect these two cars other than they won the hardest and most romantic race in the world, but what more excuse is needed to don the rose-tinted Ray Bans and bathe for a moment in the warm Sicilian sunshine?

0 comments on “Passione e follia in Sicilia”